On Earth Day, our Communications Director Sully reflects on how safe housing and environmental justice are intertwined.

When Governor Inslee kept $500,000 towards the Centralized Diversion Fund in the final state budget, we all let out a sigh of relief at A Way Home Washington. We knew that the COVID-19 outbreak meant lower revenues than expected and difficult decisions for the Governor, so we were all glad to see supports for young people experiencing homelessness remain intact. But at the same time, my heart felt heavy for the opportunities that the pandemic cost our state. It was especially hard to see $50 million towards reducing the effects of climate change disappear, because I am convinced that safe housing access and environmental justice are intertwined.

Environmental justice applies an equity lens to environmental issues. Communities of color and low-income households are disproportionately affected by issues like air pollution, industrial pollution, and climate change. The Front and Centered Environmental Justice Map shows that our state is no exception, and areas with higher numbers of people of color experience higher environmental health disparities. This is not a coincidence – it is the result of decades of discriminatory housing policies and environmental regulations that put flight paths and industrial waste dumps in these areas.

As advocates to end youth and young adult homelessness, we are working towards safe and stable housing for young people, and towards supports that help young people’s whole selves thrive. We cannot fully achieve either of these goals without environmental justice. In the past year, we’ve seen how the worsening effects of climate change are rendering homes unsafe and unstable around the world, and specifically affecting indigenous communities. In my homeland of Panama, the Guna people settled on the Caribbean coast after centuries of colonial displacement from their inland home, and now rising sea levels are displacing them once more. Bushfires in Australia wiped away thousands of homes, displacing thousands of aboriginal people and destroying their cultural sites. We cannot wait until wildfires in the Pacific Northwest push thousands of people out of their homes before we act decisively against climate change.

Displacement is just the most obvious connection between environmental hazards and housing instability for vulnerable communities. As the COVID-19 outbreak unfolds, we’re seeing the more nuanced impacts of environmental injustice on communities of color. By now, we’ve likely all heard that pre-existing health conditions, like diabetes and asthma, put individuals at higher risk of developing complications from the virus. Some have even gone the extra step and made the connection that COVID-19 is impacting Black and Latinx communities more severely because these communities have higher rates of these pre-existing conditions. But we can’t stop there. We also have to face the reason why these communities have higher rates of these health conditions – systemic racism.

Systemic racism is responsible for everything from inequitable access to healthcare to the chronic stress caused by discrimination. It’s responsible for the poor environmental conditions of areas with large populations of people of color, an underlying cause of higher rates of asthma. Pair higher rates of asthma with greater representation among frontline workers still reporting to their jobs, and many people of color face a lose-lose situation: Go to work and put their health at risk, or lose their income.

So, how can we stop environmental injustice? Just like with ending homelessness, we need to think about upstream, system-level change. Individual actions to protect the environment, like reducing our personal consumption or single-use plastics or driving less often to lower our carbon emissions, can only take us so far. We need to continue these individual actions, and also advocate for systemic change, like holding corporations accountable for negative environmental impacts and investing in mitigation efforts that center people of color.

Start your journey as an environmental justice advocate by learning about the work already going on in our state. Organizations like Front and Centered and Got Green are leaders in environmental justice to follow, centering the experiences and leadership of people of color. Let’s work together to create a world where all young people are housed, and where every young person lives in a healthy environment!

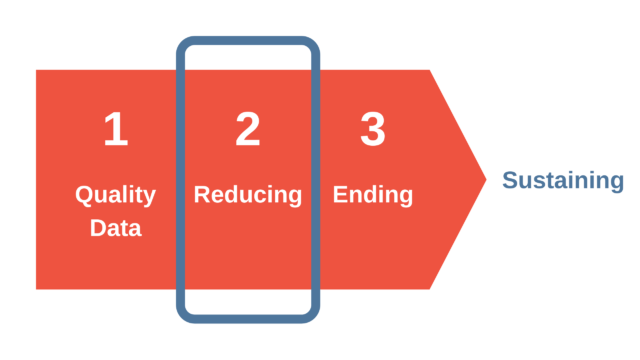

r to the Anchor Community Initiative? At a high-level, it means lowering the number of young people experiencing homelessness across the entire system. To start this process, our Data and Evaluation Director, Liz, has created different focus areas, or reducing process measures. Communities set goals around any of the following focus areas to start seeing reductions in their homeless numbers:

r to the Anchor Community Initiative? At a high-level, it means lowering the number of young people experiencing homelessness across the entire system. To start this process, our Data and Evaluation Director, Liz, has created different focus areas, or reducing process measures. Communities set goals around any of the following focus areas to start seeing reductions in their homeless numbers: